This is simply a great series and I'm sure some or many members have seen it before but it is one for the archives. I searched to see if it had been posted here before and could not find it and asked about the character limit and simply decided to put the time in.

Enjoy.

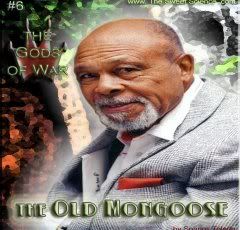

The Tenth God of War: Charley Burley

By Springs Toledo

The evening sun is sinking over the Oakland section of Pittsburgh like a great red fist in protest of defeat. An elderly man sits in a wheelchair on a front porch. There’s a scrapbook on his lap under hands gnarled by years of work and war. The hands are large. Melancholy eyes fill with yesterdays and begin to close behind his glasses as he nods off. Pages of his life come alive during these twilight dreams, and in a few moments he is burning with youth again, strong again, walking the avenue in a long coat with a cocked Stetson hat and Florsheim shoes. “Hey champ,” ghosts from the past say as he saunters by.

He was never the champ, but the whole city knows he should have been, would have been… had he only been given a chance.

Fight films click on in his head.

“I JUST WANTED TO FIGHT…”

Elmer “Violent” Ray stood 6’2, weighed about 200 lbs, and wrestled alligators in Florida for fun. With arms like bazookas, he hit hard enough to be counted among The Ring’s 100 Greatest Punchers of all time. His manager was Tommy O’Loughlin. A new fighter had recently joined O’Loughlin’s stable …a welterweight.

In 1946, Ray would drive white heavyweight contender Lee Savold into the canvas like a tent stake and was given a wide field to graze alone as a result. For years, Joe Louis wouldn’t even get in the ring with him for an exhibition.

But the welterweight did.

He agreed to spar with Elmer Ray, despite the fact that he stood only 5’9 and weighed little more than 150 lbs. Ray was a crowding, bobbing and weaving type of fighter who hurled his bulk at his opponent as if his mother’s dignity was at stake. Witnesses stated that the heavyweight threw every grenade in his arsenal but may as well have been moving in slow motion because the smaller man slipped every shot. Frustrated, Ray sought to impose his will by other means and shoved the welterweight through the ropes and onto the ring apron where he landed with a thud. All four corners of the gym noted it; the heavy bags stopped jumping on chains, the speed bags stuttered to a stop, and skip ropes dropped to the floor as a small crowd of fighters interrupted their workouts and drifted over. Managers left jabbering receivers of pay phones dangling and followed trainers to watch the welterweight climb back into the ring. The heavyweight didn’t know any better, he thought he had him now. Stomping forward with his big right hand cocked, he launched it …but it was slipped …and countered. The welterweight landed a right cross into the area of the human countenance where it says “good night”, and a left hook followed it. Elmer Ray crashed to the canvas and took an involuntary mid-afternoon nap, mid-ring.

Ray posted big wins over name fighters and became the world’s number-one ranked heavyweight contender in early 1947, but if anyone asked him who hit him the hardest, his answer was always the same: a welterweight by the name of Charley Burley.

SHAKEN, NOT STIRRED

The first crown Charley Burley went after was affixed to the head of the great Henry Armstrong. Harry Otty’s critical biography Charley Burley and the Black Murderers’ Row recounts how Burley was told by Armstrong’s management that Armstrong would not give him a title shot because he was moving back down to the lightweight division. It wasn’t true. Armstrong made a record number of welterweight defenses and Burley never got his opportunity. Fellow Pittsburgher Fritzie Zivic fought Burley three times, earning a dubious decision in the first contest and then losing twice afterwards. Although he was ranked behind Burley, it was Zivic who got the title shot against Armstrong. And it was Zivic who went to comedic lengths to avoid facing Burley again as champion –he bought Burley’s contract and became his manager. Only after he lost the title did he sell Burley’s contract to Tommy O’Loughlin for $500. This happened in 1941. Zivic’s successor, Freddie “Red” Cochrane declined to fight Burley even though Burley offered to fight him for free.

Early in 1942, Al Abrams of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported that Tommy O’Loughlin wired an offer of $7500 to light heavyweight champion Billy Conn’s manager for a fight with Burley in Minneapolis. The offer was laughed at. Conn might have remembered those early sparring sessions in Pittsburgh that were the talk of the black community.

Middleweights were no braver. There is a persistent rumor that holds that Marcel Cerdan considered facing Burley when he arrived to the American shore, but after seeing Burley beat up on his sparring partners, he lost interest. Burley was forced to contend for frivolous titles like the so-called “Colored Middleweight Title” and the “California State Middleweight Title” against other African American fighters almost as great and just as forgotten as he is.

Burley’s mother was Irish, but he wasn’t quite white enough; and he was far too good for his own good, so public challenges were unmet, phone calls unanswered, and managers went deaf the moment his name was uttered. “I’d go anywhere to fight anybody,” Burley said, “if they’d get somebody for me I’d fight them. I just wanted to fight …I knew I could have held my own against anybody, that’s the God’s truth.” O’Loughlin took that at face value. He figured that if the iron of three divisions wouldn’t face Burley, perhaps the giants would. To really turn heads, he decided to pit Burley against a 6’3 journeyman in JD Turner who had just gone the distance with Conn. After obtaining permission from the Athletic Commission of Minnesota for Burley to fight a heavyweight based on the reasoning that Burley was having difficulty finding willing opponents in his own weight class, Burley climbed through the ropes to face a man who was 68½ lbs heavier. It was a physical mismatch and a novelty. It was also a rout. In the opening seconds, Burley landed a right cross that crossed the eyes and rattled the teeth of Turner. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported that from that moment to the end of the sixth round, Burley was “his master, punching and batting the big Texan at will.”

JD Turner didn’t answer the bell for the seventh round. “That little sucker,” he said, “–knocked me cold. I woke up in the dressing room.”

A week later, O’Loughlin walked into the Pennsylvania Boxing Commission to get another waiver, this one to overcome a local rule forbidding fighters weighing less than the light heavyweight limit from facing opponents who “greatly outweigh them.” Burley, ranked fourth in the welterweight division, was looking for a fight against Harry Bobo, a 6’4, third-ranked heavyweight whose nickname was “The Paralyzer”.

THE WILD WEST

Nothing came of that. So he went west, where the wild things were. In the 1940s, California was the scene of an alternative boxing universe where Burley joined African American fighters like Eddie Booker, Lloyd Marshall, Jack Chase, Bert Lytell, and Aaron “Tiger” Wade. Budd Schulberg dubbed the group of them “Black Murderers’ Row” and boxing historian Harry Otty added Holman Williams and Cocoa Kid to their mythical ranks. These eight fighters faced each other 61 times. Burley came out of their round-robin tournaments with the best record, going 10-5-1 with one no-contest. All of them were notoriously tough and durable and none of them managed to win by knockout

Sugar Ray Robinson was no more eager than any other champion to face these fighters, but he did use Cocoa Kid and Tiger Wade as sparring partners in the late 1940s. Tiger Wade was semi-retired when he separated Robinson’s sixth and seventh ribs during a session in 1948. Inactive and thirty-six years old, Cocoa Kid dropped a peaking Sugar Ray with an overhand right in the gym during the summer of 1949. This occurred after Robinson, according to the Long Beach Press-Telegram, was accused by a promoter of “evading his obligations” and breaking an agreement to fight Cocoa Kid in April.

…In other words, Sugar Ray ran out on Cocoa Kid.

His problems facing and/or handling these fighters are documented. But then, Robinson’s greatness is unquestionable. Wade found out the hard way after signing to fight Robinson for real in 1950. After going down five times inside of three rounds including one airborne trip out of the ring, Wade’s career ended with him on his hands and knees after Robinson landed a déjà vu shot to his ribs.

|

|

Thanks:

Thanks:  Likes:

Likes:  Dislikes:

Dislikes:

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks