Continuing on with part one...

Moore improved on this already comprehensive design by adjusting the positioning of his body, furthering the ability of his arms to cover and protect. Pulling his head back and sinking into his right hip, Moore could bring his left shoulder and elbow up to cover the line of his chin, or he could shift to his left hip and raise his right elbow to defeat an incoming left hook. Moore also discovered that by changing levels, crouching and rolling with his upper body, his head, shoulders, and crossed arms would obstruct the opponent's line of sight, enabling him to sneak punches in from unexpected angles.

This ability to obfuscate and disguise intentions is perhaps the best and most underappreciated element of Archie's Lock. For we can't ignore the fact that, with both arms crossed over the body, a boxer is not in prime position to attack. "Barring" was more immediately viable in the bare-knuckle days whence it came to prominence, because Broughton's Rules, which governed the sport, allowed virtually every kind of hand strike.

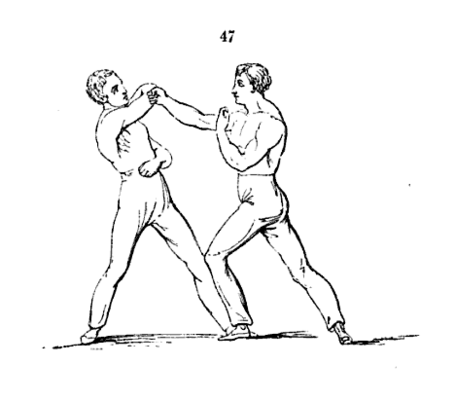

Donald Walker, Defensive Exercises, 1840

Here, a boxer bars a straight right from his opponent, leaning back as he does so. Note that the knuckles of his right hand are turned out as he draws his hand fully across, over his left shoulder. The author of this manual, Donald Walker, writes that this position is especially useful for "the Mendoza style", by which he means Daniel Mendoza, arguably the very first "scientific" boxer. Mendoza was well known by his fondness for a blow called "the Chopper," a backfist which was brought swinging down onto the face of the opponent from precisely the position shown above.

By the 1880s, glove boxing and the new Queensbury Rules that governed it put an end to such "unmanful" strikes as the Chopper, prohibiting boxers from striking with any part of the hand but the fore-knuckles. The most obvious counter from the cross-armed guard illegalized, another method of attacking from this defensive shell would need to be devised for it to remain viable.

Back we go to Moore's adaptation, or rather the adaptation of Moore's era, as boxers like Paolino Uzcudun were using similar tactics years before the Old Mongoose came to prominence. As I mentioned above, Moore's system was based on body movement. Ducking, rolling, turning, and slipping, Moore would hide his weapons from his opponent's sight. Turning to his right, he would hide his right hand behind his left shoulder. Turning left, he would lower his head and hide his left under his right arm. He would also use his crossed arms from this position to lever his opponent on the inside, creating space to throw his punches.

If one were really desperate for historical comparisons, one could trace this facet of Moore's style all the way back to sword and buckler fencing, in which the buckler, a small shield, was used less for static defense and more as a means of hiding one's sword from the opponent, thus preventing him from reading the attack. This folio, from Royal Armouries Manuscript, shows the concept clearly.

Many of the bare-knuckle boxing manuals referenced already contain sections on swordplay, so this connection isn't as much of a stretch as it may seem at first. Given the fact that English boxing stemmed directly from rapier and smallsword fencing, however, not sword and buckler, and the fact that there were several well-established schools of pure boxing by the end of the 19th century, it is more likely that Moore's application of the cross-armed guard developed wholly within the sport of boxing itself. Still, the connection is intriguing.

So ends part one of this analysis. With the history of the Lock out of the way, tomorrow I will be using videos and GIFs of Moore and his various stylistic descendants to analyze the facets of his particular system. At the risk of making it sound too exciting, I'll tell you this: there's a flow chart. Make sure to check back tomorrow morning for that!

Continue onto part two in the next post...

|

|

Thanks:

Thanks:  Likes:

Likes:  Dislikes:

Dislikes:

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks