| Remember the night Mike Tyson lost to “Buster” Douglas? Often called the greatest upset in sports history, Douglas, a 42-1 underdog, shocked the world and Don King in front of a reserved Tokyo audience with a stunning tenth round knockout. Nobody believed that anyone, let alone a journeyman heavyweight fighter, could defeat the |  |

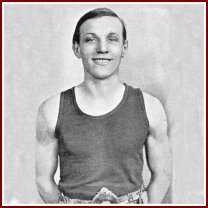

twenty-three-year-old phenomenon. So imagine how astounded they’d be to learn that the wheels for that loss were set in motion by a five-foot-tall, 100-pound, pale, skinny fighter from the tough little mining town of Merthyr Tydfil, South Wales over seventy years earlier. Born in 1892, Jimmy Wilde started work as a miner around age twelve and built up an amazing strength for his size. He put that juice to good use in the many boxing booths popular in the United Kingdom at that time where he could earn a weeks mining wage in just one night of fighting. Despite his size (or lack of it), Jimmy was a crowd favorite due to his knockout punch, courage and toughness. He turned professional at sixteen and was unbeaten in his first 101 contests, many against opponents out-weighing him by twenty-to thirty pounds. Wilde earned many nicknames (always a good sign), among them: “The Mighty Atom,” “The Ghost with the Hammer in His Hand,” and “The Tylerstown Terror.” He became the first universally recognized flyweight champion, celebrated on both sides of the Atlantic with Gene Tunney calling him, “the greatest fighter I ever saw.” His career record stands at 131 wins, with only three losses and an incredible ninety-nine knockouts. Many call “The Tylerstown Terror” the greatest flyweight of all time and he is commonly ranks in the best five punchers in history of the sport, pound-for-pound.

Here we trace how the hardest punching flyweight, who died in 1969, beat the man, who beat the man, who beat the man, and so on until we meet the man who eventually handed Mike Tyson that spectacular loss.

London, July 19, 1919. Memphis Pal Moore, a tough bantamweight from Tennessee was brought in to fight Jimmy Wilde. A former title claimant, Moore had eighty-three wins and beat many illustrious fighters. However, he was no match that night for Wilde and would lose a unanimous decision over twenty rounds. Memphis was only six years in to his seventeen year career and in 1922, would fight, and beat, Charles “Bud” Taylor onboard the USS Commodore via a newspaper decision. Back in 1920’s America, when the Christian Coalition was banning everything from boozing to boxing, fights were only allowed to go ahead as exhibitions in many states. Newspaper reporters would generally confer after the fight and report their winner in the next day’s journal. In this case, Moore was the scribes’ choice as victor in a big upset.

Charles Taylor was known as “The Blonde Terror of Terre Haute,” presumably because he was blonde and from Terre Haute (and a little terror, to boot). At the time of the Moore loss, he had been fighting less than two years but would go on to have a Hall of Fame career, meeting, and beating such greats as Pancho Villa (who beat Wilde), Abe Goldstein, Jimmy McLarnin (he was the first man to defeat the Belfast Spider), Tommy Ryan, Tony Canzoneri, Al Singer, Fidel LaBarba, Benny Bass and Battling Battalino, whom he vanquished in Detroit in March 1930.

A sometimes shady fighter from Connecticut, Battalino could be involved in amazing give and take battles, such as his featherweight title winning effort against the copasetic Kid Chocolate, or could be embroiled in controversy amid accusations of diving in others. When straight, he managed to beat many excellent opponents including the Cocoa Kid, whom he kayoed in seven rounds in 1934.

Born Louis Hardwick in Puerto Rico, Cocoa was a tall welterweight fighter who mixed with top company over his eighteen-year career. While never a world champion, he did manage to become the “colored” welterweight champion (a belt only recognized in segregated America) by defeating Holman Williams in 1940. Hardwick, along with Williams and Charlie Burley are often considered the three best fighters never to win world titles, being frozen out because they were too good and too black, often having to fight each other several times in a bid to stay engaged. Cocoa Kid fought Williams a recorded four times, winning three, while Williams would battle Charlie Burley seven times, winning three apiece.

Another great African-American also frozen out during this period was Archie “The Old Mongoose” Moore, who holds the record for the most career knockouts (131). Moore split two fights with Holman Williams and fought for seventeen years before he was even given a shot at a title, winning easily on points against Joey Maxim. This shot only came about due to Moore’s incredible longevity and a marketing campaign during which he continuously wrote to all U.S. newspaper editors promoting his cause. Archie’s achievements need no explanation and he is on every pound-for-pound list in history, eventually fighting for almost thirty years, holding the light heavyweight title for ten and decking Rocky Marciano in a heavyweight title bid when he was into his forties. He beat most of the top fighters from middleweight to heavyweight during the 1940’s and 1950’s, including Nino Valdez, the heavyweight Cuban KO specialist.

Beginning his career in Cuba, Valdez would become a fight fan favorite all over the U.S. and Europe, winning and losing against the top contenders of the day. Among his victims was the undefeated Joe Erskine from Wales, of whom the British held high hopes of a championship belt. In an astounding upset, Valdez stopped the home fighter in the first round, effectively ended the Welshman’s top-level hopes. Erskine would go on to become British and Commonwealth (then called the British Empire) champion with a points win over Henry Cooper in fifteen rounds, although our ‘Enry would avenge that result with three knockout wins. His penultimate win was against a young fighter from Derbyshire named Jack Bodell, whom Harry Carpenter, Britain’s most famous Boxing commentator, would introduce as, “the chicken farmer from Swadlincote.”

Bodell, an unassuming, often awkward man, was another fighter thwarted at championship level by Henry Cooper, although he did defeat Cooper conqueror Joe Bugner in a bout that caused a major shock in U.K. boxing circles. This victory proved Bodell’s downfall as he lost his next three fights in a total of five rounds against Jerry Quarry (knocked out in one), Jose Urtain (two) and Danny McAlinden for his British and Commonwealth belts won from Bugner.

Boxing enigma Joe Bugner was born Hungary in 1950, and moved with his family to England during the Hungarian uprising against the Communist occupation in 1956. A solidly built heavyweight with good skills and fast hands, he lost his professional debut by knockout and then suffered only one reverse in his next thirty-three bouts before meeting Britain’s favorite boxer, Henry Cooper for the British and Commonwealth title. Bugner won an extremely unpopular referee’s decision against the thirty-six-year-old champion (Cooper, in disgust, never fought again), and then won the European title against future Ali opponent, Jurgen Blin. Again, the British thought they had a big heavyweight who could challenge the top Americans, but their excitement soon turned to dismay when Bodell, by now in his thirties and with ten losses on his record, out-hustled a lethargic Bugner in London in 1971. Bugner’s career was a frustrating one for his fans, with some good, solid performances against Joe Frazier and Ron Lyle mixed in with indifferent efforts against lesser lights. He was often bemoaned for a lack of endeavor and the reporters scorn was highlighted after Joe’s boring, and lazy, loss against Muhammad Ali. When British writers criticized his performance, Bugner screamed, “Get me Jesus Christ! I’ll fight him tomorrow.” to which Hugh McIlvanney of the London Observer replied, “Ah, Joe, you’re only saying that ’cause you know he has bad hands.” Bugner would fight on and off until1999 with mixed results, although he still had too much know-how for nine fight novice Anders Eklund, a Swedish fighter based in Denmark, in 1984.

Eklund was a typical European heavyweight, lacking fluidity and stamina, but making up for it in courage and matchmaking. He lost against every upper tier opponent he met but beat the usual trial-horses including Jesse “The Boogieman” Ferguson from Philadelphia, whom he out-pointed in October 1986. Ferguson met every name heavyweight of the 1980’s & 1990’s, being used as a yardstick for up and coming prospects. His five minutes of fame came back in 1993 when television microphones overheard Olympic Gold Medalist Ray Mercer trying to bribe Ferguson during a fight at Madison Square Garden. Jesse went on to win a close decision but lost the resulting rematch. Ferguson would fight eleven guys who would challenge or win the Heavyweight title and was competitive in many including an early win against one James “Buster” Douglas.

“Dynamite” Billy Douglas was a “give all, take all” middleweight / light heavyweight from the 1970’s who could never quite beat the top fighters, suffering losses to Bennie Briscoe, Willie Monroe, Victor Galindez, Mathew Saad Muhammad and Marvin Johnson but making up in heart and entertainment value what he lacked in skills. His son James, nicknamed “Buster,” had more than enough talent to make the grade, but not the hunger that drove his father. Turning down an opportunity to pursue a college BA degree, he turned pro in 1981, aged twenty-one, and built up a record of 18-1-1 before succumbing to Mike “The Giant” White by ninth round technical knockout; a fight he was winning handily against a fighter on a four-fight losing streak. He followed this with five wins in his next eight fights before embarking on a six-fight winning streak, including ten-round unanimous decision wins over Trevor Berbick and Oliver McCall in 1989, but many questioned his desire for his chosen profession.

Meanwhile, Michael Gerard Tyson was burning up the heavyweight division like no fighter before. Turning professional in March 1985 at just eighteen-years-old, he swept through a moribund sea of overweight and lazy pugilists, scoring twenty-five knockouts in a twenty-seven-fight streak culminating in a two round destruction of Trevor Berbick in November 1986, just twenty-one months after turning professional. He then unified the division and cleared away all challengers until only one fighter came even close to having a chance against “Iron” Mike. That man was cruiserweight champion Evander Holyfield. Before that, Mike would fly to Tokyo for an easy money defense versus Buster Douglas. In an incredible upset that every fight fan is aware of, Douglas won by tenth round knockout, leaving Tyson’s aura of invincibility crawling on its knees in a Japanese ring. Neither man reached such heights again, with Douglas losing in his next contest while Tyson’s many troubles are well documented elsewhere.

So there you have it, a direct link of fifteen wins from Jimmy Wilde to Mike Tyson, proving that sometimes a good little ‘un can beat a good big ‘un. It just takes a while.

Rupert Wricklemarsh can be reached at taansend@yahoo.com

Boxing News Boxing News

Boxing News Boxing News